Your Legal Resource

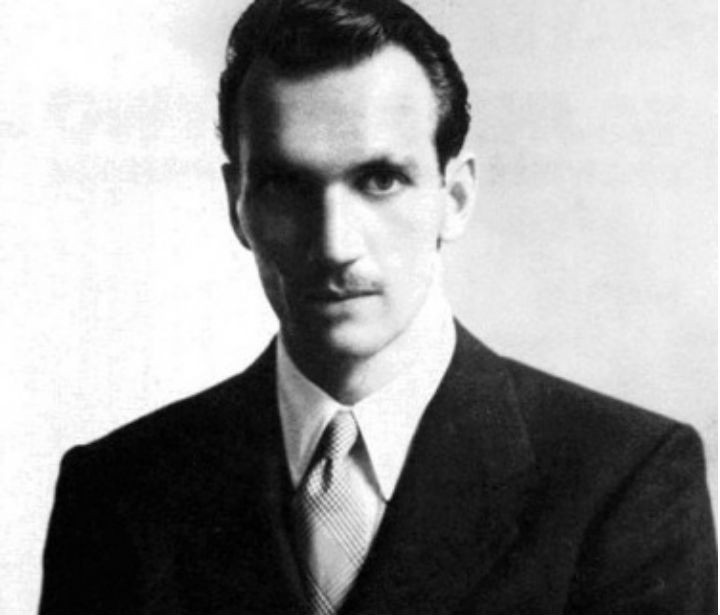

U.s. Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter Didn't Believe In The Holocaust

Polish courier delivered unheeded messages on Holocaust

STANFORD -- Jan Karski easily could have wound up being one of the 3 million ethnic Poles who were murdered by Nazis in World War II concentration camps. Instead, he became an emissary for the Polish underground and was one of the first non-Jewish eyewitnesses to the Holocaust to tell Western leaders about Hitler's extermination of European Jews.

Some of those leaders found the horrifying stories hard to believe, Karski told an audience at Stanford Monday, March 6. And when the wartime leaders of England and the United States did take seriously his accounts of life and death in the Warsaw ghetto and the Belzec concentration camp, they generally found reasons not to intervene directly.

While Karski considers his attempts failed, he is generally credited with personally persuading President Franklin Roosevelt to create the War Refugee Board, which eventually helped many Jews.

Karski was smuggled into London and Washington, D.C., to deliver messages on behalf of the Polish underground as well as Jewish groups, he said. With some officials, such as Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden of Great Britain, the conversations were limited to Polish issues, and the question of the Jews was never raised, said Karski, now 81.

But during a meeting with U.S. Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter in 1943, Karski said, the adviser to Roosevelt pointed out that he was Jewish, and asked what was happening to Jews in occupied Europe.

Karski gave his firsthand, candid account, answered a number of "technical questions," and then Frankfurter said, "I am unable to believe what you have told me."

A Polish diplomat intervened, asking Frankfurter whether he thought Karski had lied.

Saying he remembered the event vividly, Karski recalled that Frankfurter then began to pace the room. After a time, he said, "I did not say that this young man was lying. I said that I was unable to believe what he told me.

"There is a difference."

Nearly 200 people jammed the Oak Room at Tresidder Union to hear Karski, who delivered the second Konstanty and Antonina Stys Lecture for Humanistic Studies in Polish History and Culture, sponsored by the Center for Russian and East European Studies.

In introducing Karski, Norman Naimark, professor of history and director of the center, said the speaker was "a living embodiment of the Polish humanistic tradition." Naimark also noted that Karski's attempts to help the Jews was the subject of a recent biography, Karski: How One Man Tried to Stop the Holocaust, which Naimark called "a moving, absorbing" story.

Karski, professor emeritus of political science at Georgetown University, also published his own account in 1943, Story of a Secret State.

Karski was a young Polish diplomat when Germany invaded on Sept. 1, 1939. He joined the Polish army but was captured by the Red Army when the Soviet Union attacked from the east. He escaped and joined the underground, and became a courier between the underground and Poland's government-in-exile.

The Gestapo arrested Karski in 1940, but he was freed by the underground. After being smuggled twice into the Warsaw ghetto and once into Belzec, he was sent on a treacherous journey to deliver pleas for Allied action.

To get to England, Karski said, "I had to cross 39 boundaries, each one illegally.

"I met with many powerful leaders in London and Washington," Karski said, but he didn't feel comfortable arguing with or challenging those leaders. With Eden, for instance, Karski dared not initiate a discussion of the Holocaust.

"I was a nobody during the war," he said. "I was a little, anonymous agent. My superiors were saying, 'Don't provoke, don't antagonize.'"

So Karski said he gave his reports, "answered questions if I knew the answers" and prayed for action. The Allies' failure to take direct action to stop the Holocaust could have been based on several factors, Karski said.

First of all, "Perhaps it [the Holocaust] did seem unbelievable. What happened to the Jews was unprecedented; humanity was not prepared for it, and the Jews were not prepared for it."

After the war started, he said, "The Jews in Europe were totally helpless; they had no government, no country, no representation at the inter-ally conferences."

Even when reports of the Holocaust were becoming more common, and leaders had more reason to believe Karski and Jewish American leaders who were demanding action, "by that time, the basic Allied war strategy was already determined."

That strategy was for the total defeat of Germany as soon as possible, with unconditional surrender. Re-directing war resources was not considered, he said.

In addition, Churchill and Roosevelt had to appease Josef Stalin of the Soviet Union, who was impatiently waiting for a second front to be established with the invasion of Europe. The two Western leaders, Karski said, desperately needed Stalin's help to defeat Japan, and he was unwilling to accept any delay from the West.

After Hitler's defeat at Stalingrad in 1943, the turning point in the Eastern war, it became clear to Churchill and Roosevelt that they would be dealing with a post-war Stalin who held complete and absolute rule in what would clearly be a superpower. Reaching agreement with Stalin, Karski said, "became one of the highest priorities for the Western Allies."

Karski did have a face-to-face meeting with Roosevelt in 1943, and while he considered it a failure - he did not talk about it during his lecture - others say it led directly to the president's creation of the War Refugee Board.

While in England and the United States, the young Pole - whose code name was "Witold" - also met with numerous other politicians and lobbyists, Catholic bishops and cardinals, leaders of the European underground, and authors such H.G. Wells and Arthur Koestler (Darkness at Noon).

"The Catholic leaders were friendly," said Karski, himself a Catholic. "They blessed me, and asked questions about the church's losses and whether the people maintained their faith.

"None of them asked about the Jews."

When meeting with State Department and War Department representatives, Karski said, he delivered requests and demands for various actions on behalf of European Jews. All were refused, he recalled.

"Whatever demand I submitted on behalf of the Jews, [the response was], 'impossible.' "

On Jewish calls for Allied leaders to make a public declaration that stopping the Holocaust becomes part of the official war strategy, Karski was told that it would only reinforce German Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels' contention that World War II was provoked by Jews and that Western nations were suffering on their behalf.

On suggestions that Germans be notified about the Holocaust via bomber-delivered leaflets, he was told that each sortie was too critical to consider carrying anything other than bombs.

On Jewish demands to bomb railroad lines leading into Auschwitz, he was told that the rails would be quickly repaired - by Jewish prison laborers, many of whom would die in the effort.

On requests for U.S. visa forms that could be delivered to the underground and forged to save the lives of Jews, Karski was summarily dismissed by Charles Bohlen, an envoy who would later become ambassador to Moscow and Paris: "That would be a violation of federal law."

Overall, Karski said, "Everybody sympathized with the Jews, but the Jews were abandoned."

However, he said, "My message is, the Jews were abandoned by governments, by churches, by societal structures - but not by humanity. Thousands of individuals - in Poland, in Belgium, in the Netherlands, in Greece - were trying to help the Jews.

"Don't believe that humanity betrayed the Jews."

Many Poles, he said, assisted Jews even though there was an automatic death sentence in occupied Poland for anyone caught doing so. (At the same time, in many regions, Karski said Poles who informed on Jews in hiding or collaborators were offered a "bounty" of one liter of vodka.)

Speaking shortly after the 50th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz, Karski said Jews and non-Jews alike must continue to remind future generations not only of what happened but of the people like himself who tried - and failed - to alter the course of history.

"Let it always stay in the human memory," he said.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------